THE MARE KNEW SHE WAS BEING WATCHED. She stood in a corner of her stall and pretended not to notice the man leaning on his forearms against an iron fence, examining her every move, but her swishing tail and tense ears gave her away. That’s what the man was looking for: clues to her disposition. His name was Gil Stoner, and he was to be her trainer for the next two months. She was new to the Stoner Ranch, two thousand hardscrabble acres of rocks and brush on the rim of the Hill Country northwest of Uvalde, and Gil was doing what he always does when a client sends him a new horse to train: spend a lot of time just watching. He can evaluate its physique in a matter of moments. The hard part is evaluating its mind.

“Horses aren’t the brightest animals in the world,” he said, “but they have unbelievable feel. And they’re willing. They’ll do whatever they’re able to do. What I do all day is try to be just a little bit smarter than a horse.”

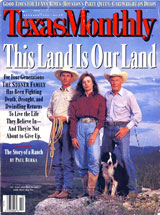

At 37, Gil Stoner has spent most of his life figuring out horses. He was riding at the age of 2, roping at the age of 4. For as long as he can remember, he has wanted to live out his time on earth on the family ranch, as his father is doing, as his father’s father did, as his great-grandmother did, as Stoners have been doing for 112 years.

But time may be running out on families like the Stoners—small ranchers who cling stubbornly to the land they were born on. Ranching is a marginal business in the best of times; when Gil was majoring in ranch management at Texas A&M, he learned that the rule of thumb for investing in livestock was a 4 percent return. You have to own a lot of livestock, and a lot more acres than the Stoners do, for 4 percent to amount to much. Today, fewer and fewer ranching families actually live on their land and raise their children there; more and more are leasing their property and moving to town, where life is more comfortable and work is less demanding. You have to have an unshakable faith in the intangible values and rewards of ranch life to keep going, and Gil does. But he knows that if the Stoner Ranch has a future, it won’t involve traditional ranching.

Cattle and oil, which have supported successful Texas ranches for most of this century, have never played a role at the Stoner Ranch. The land is, and always has been, sheep and goat country; beef cattle can’t make it here. As for oil, the total production in the history of Uvalde County is a minuscule 1,814 barrels, not a drop of which has occurred since 1986. During the oil boom someone actually leased the mineral rights to the Stoner Ranch, but nothing ever came of it. About the only option left is horses.

The Nueces River Canyon, though, is not exactly horse country. It is too far from the big cities, where well-heeled professionals buy horses for their kids and dream of owning a place like the Stoner Ranch—not for working, but for relaxing on weekends. It is also too dry, even in years of normal rainfall. Now, when the Stoner Ranch has received just two inches of rain from early November to late August, the land is so parched that not a green clump of grass can be seen. Dust seems to be suspended in the air. It adheres to your lips, gets under your hat, settles onto your clothes, and explodes in clouds when you pat Tex, the ranch’s senior Border collie. Horse ranching in the Nueces River Canyon doesn’t mean a big breeding operation with lush pastures, handsome stables, a big staff, and a gleaming white house. For Gil, it means taking in other people’s horses to train, having a spec horse or two of his own, doing all the work himself, and living in a rock cottage built by his grandfather in 1940, where only the living room is air-conditioned and he and his wife, Amy, got an evaporative cooler for their bedroom just last year.

Gil trains horses, but he doesn’t like being called a trainer, which sounds too much like an employee. “Call me a horseman,” he said, never taking his eyes off the mare. finally, she swung her neck around and inspected him with her left eye. Before her stood someone a little short of six feet tall and cowboy-skinny. He wore jeans, chaps, and a blue long-sleeved work shirt that was torn and faded from hard use. His longish face and high cheekbones were Stoner family traits, but his most striking feature was a pair of unsentimental, appraising eyes. His wide-brimmed white straw hat seemed to be part of his body, so seldom did it come off; three days would pass before I discovered that he had short black hair. Apparently he passed the mare’s inspection, because she walked over to him in that slow, ambling way horses have that indicates approval. Gil allowed her to stop and pick her position before he reached between the rails and scratched her belly. “I’ve found this spot that she likes,” he said. The mare smacked her lips, over and over, as if she were chewing gum.

Together they made the most durable of Western images, the man and his horse. But it was a variation on the old theme. They were two of a kind, really, both looking for a way to survive in the modern world. The mare was no good for racing and no good for breeding; her owner wanted Gil to make her into a pole and barrel horse that his daughter could ride in rodeos. The mare’s quarter horse skills are no longer in demand outside of the entertainment business. Gil too is in the entertainment business; when he isn’t training horses, he’s holding weekend clinics to teach kids how to ride or rope. He has taken in campers, backpackers, even a Belgian tourist who wanted to learn the Western style of riding. Anything to hold on to the land.

THE STONER RANCH EXTENDS eastward from the Nueces in a rectangle, first over a mesquite-choked plain, then up and across a line of hills that bring an abrupt end to the river valley. This is not the Hill Country as most Texans know it—that benign and beloved land of gentle slopes covered with scrub oak and cedar, broad plateaus, and streams that flow swift and cold and clear over limestone bedrock. Here the Nueces runs slow and sluggish, when it runs at all; occasionally it disappears beneath gravel beds, turning its bottom into a desert wash. The mouth of the canyon, about ten miles south of the Stoner Ranch, is one of Texas’ great geographical crossroads: the intersection of the brush country, the Hill Country, and the Chihuahuan Desert. Invader plants have forced their way into the lower canyon and taken over the land—cursed species found nowhere else in the Hill Country, like the sharp-toothed sotol and ground-hugging, clawlike lechuguilla. This is rough country, magnificent in its unyielding harshness. The hills are like mountains in miniature: their flanks precipitous, their upper elevations encircled by vertical bands of rock, their crowns barren. Indeed, the first settlers in the canyon called them mountains, and mountains they are still called today. “You’d call ’em mountains too,” Gil told me, “if you had to climb ’em or ride up ’em.”

He was showing me around the ranch in a red pickup. Actually we were going to see only the part closest to the river. The back pastures, amounting to two thirds of the property, have been leased to a neighboring ranch for grazing since 1982. A hunting lease covers the same acreage and brings in more money than the grazing lease, which is a good indication of the suprem-acy of recreation over agriculture these days. Altogether the leased land generates less than $20,000 a year, and Gil was worried about the future. “We may not have a grass lease next year,” he said. “What are we going to lease them? Rocks?”