The part of the ranch occupied by the Stoners includes the riverfront, two houses, a barn area for the horses, and some very unpastoral pastureland, where Red Stoner, Gil’s father, keeps a flock of sheep. He lives in the rock house with Gil and Amy; Gil’s mother, Robbie, lives in the older frame house near the river. When Gil was in the third grade, Robbie decided to take all three children—Gil, his twin brother, Tom, and his sister, Jamie—to Houston because of concern about dyslexia in the family. Red didn’t want her to go, and of course, he had to stay. The boys came back to the ranch on weekends and for summers—“They knew our first names on that Greyhound bus,” Gil told me—and returned for good when they were in high school. Gil went from a sophomore class of 2,000 students to a junior class of 37. Robbie, though, stayed in Houston as a nursing instructor. When she retired, she moved into the other house.

Gil stopped the pickup on the river-front. We were in a grove of thick-trunked pecans, the tree that gave the river its name (“nueces” is Spanish for “nut”). But because of the drought, there would be no nut crop this year. He pointed to a bare patch of earth, a clearing between two groves of trees. “You’re not supposed to see the ground out here,” he said. “Even the weeds wouldn’t grow this year. If you see anything that’s still green, it’s poisonous.”

Earlier this summer the well by the ranch house went dry—the first time that had ever happened. Gil and Amy had to haul buckets of springwater from the river by truck until they could get the well deepened from 45 feet to 85 feet. “Drought is hard on everybody,” Gil said. “The horses don’t want to work. You can see deer and jackrabbits out in the middle of the day looking for food.”

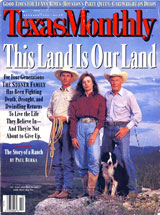

We had stopped, he told me, at the place where he and Amy had gotten married two years ago. Amy, who is ten years younger than Gil, had already given me the details. She had grown up in Uvalde and moved to Austin after graduating from high school. Three days later she came home. She met Gil at a restaurant—her date had invited Gil to sit with them—and again a year later at a dance. The first thing she noticed when he asked her to dance was that his foot was in a cast. The second thing she noticed was that it didn’t slow him down. When they got engaged, Amy’s mother said that she had always known that Amy was born to live on a ranch because she loved animals so much. At the wedding, Amy arrived by horse-drawn carriage and Gil rode in on his horse.

Today the area is a campsite used by visitors, some invited, some uninvited. “People come right up the river with their four-wheel drives,” Gil said. “They come up here drinking beer, and each mile they go, they get a little smarter. They know their rights, but they won’t respect mine. They set up camp in the river and cross my fence. Once they were giving some of my campers a hard time, and I came down and asked them to leave. One fella said, ‘I don’t think you’re big enough to make me.’

“He was right—I wasn’t. I went back to the house and called the deputy sheriff. I told him, ‘Nobody is going to talk like that to me on my own land. You better get out here. I know where my gun is.’

“It breaks my heart,” he said, “to see this beautiful land get trashed up.”

ANNA LOUISA WELLINGTON STONER wasn’t so taken with the land when she first saw it at the age of 24. She and her husband, William Clinton Stoner, had come to the Nueces River Canyon from Victoria in 1881, looking for a dryer, healthier climate. Traveling by wagon with their two young children, they crossed the property that would one day bear the family name—and they regarded it and the rest of the lower canyon as the worst land they had seen on their journey. The land improved as they continued upriver, and for four months they stayed with another family, living in a tent while Clinton looked for a place of his own and hunted wild game for his family to eat. Once they dined on bear. Clinton considered moving to Kerrville or Bandera but eventually decided to head farther up the Nueces into Edwards County, of which the Texas Almanac had written a few years earlier, “Very few, if any, have had the temerity to try to live there.” In the 1880 census the county had a thousand square miles but just 266 people.

Clinton moved his family onto vacated land that had a log house, a springhouse, a smokehouse, and a garden. Who the original occupants were or why they abandoned the homestead is unknown, although there were ample reasons for them to leave: renegade Indians (the area wasn’t secured until 1882), outlaws and other undesirables who had retreated into the remote upper reaches of the Nueces, and the lack of nearby towns or adequate roads. In December 1882 Clinton made the arduous journey to Uvalde to meet visiting relatives arriving on the newly built railroad. The weather was warm and he disregarded Anna’s advice to take a coat; sure enough, a norther blew through and he caught a bad cold, which settled into his lungs. Thirteen months later he was dead, struck down by pneumo-nia and overwork. He left Anna a little money, some hogs, around five hundred goats—and pregnant. Her seven-year-old daughter and five-year-old son had to do the ranch work while she took care of the baby, who was born six weeks after Clinton’s death and contracted infantile paralysis. Thieves preyed on the new widow, stealing her livestock. That summer, Anna decided to look for land down-river in more settled country, and in October 1884 she bought 320 acres, half a square mile, on the Nueces—the beginning of the Stoner Ranch. She would live on the land for another 69 years, until 1953, when she died at the age of 96.

It is rare for so many details to be known about a pioneer family, but Anna was a prolific correspondent. She wrote to her mother and brother back in Victoria, and they kept each other’s letters. When Anna’s mother came to live with her after Clinton got sick, the letters were united in a single collection, which Anna kept in a trunk. A devastating flood in 1913 swept the house away, but the trunk was saved, its contents covered with silt but still readable. Anna wrote letters into her nineties, using a magnifying glass to aid her eyesight. Her granddaughter donated the letters to Baylor University, and they became the subject of a book, Letters by Lamplight, by a graduate student named Lois Meyers. If anyone wonders why Gil chooses to live a life that most city folk would consider desperately hard and isolated, the answer must start with his great-grandmother Anna.

She was under no illusion about the fecundity of the country. In her first letter home, while she and Clinton were living in a tent, she wrote her mother, “This part of the canyon is very pretty, but we thought of all the God forsaken places on earth, the part we came over to get here was the worst.” Even the better land, where they were living temporarily, “looks as if it wouldn’t feed a goose to the acre.” Her description of the Nueces canyon would do it justice today: “I just tell you,” she wrote her mother, “if you will cover the whole face of the earth with low thorn bushes that will average as high as chaparral down there & put bare mountains and rocks all through it, you will about have it.” Clinton’s father came from Illinois to visit them and was so dismayed by the inhospitable conditions that he offered his son 52 fertile acres, animals, and farm implements to move back to Illinois. Anna’s brother was equally unimpressed. He wrote his mother that the land couldn’t sustain cattle or sheep, but “for goats, rattlesnakes, and rabbits, it is the finest place I ever saw in my life.…Some people here pretend to think that this is a heaven on earth, but they will all offer to sell at one dollar or rent their land at two cents per acre.”

Yet she stayed after Clinton’s death, probably because she had nowhere better to go—certainly not back to Victoria. Evidently something in the family history distressed her. “Be up & stirring,” she once wrote her brother. “You know what the past has been & what the present is now. Make the future something better. We have all depended too much upon what others said, thought, & did, that has been a family failing with us…I couldn’t see it at one time, but now I can & I have concluded that God hates a fool & lazy person, so I have determined not to be either any longer.”