“DO YOU WANT TO SEE THE BACK PASTURE?” Red asked me. A friend named Carl had dropped by to watch the roping and when the session had come to its sudden end, he had offered to give Red a hand with some fence mending on the leased acreage. As we got under way, I noticed that Carl was pressing the driver’s door shut with his left arm. The four-wheel-drive truck looked and sounded as if it wouldn’t do twenty miles an hour on a good day, but that was about eighteen more than we could use on the road that ascended the hills. It was all rock—no dirt at all. First it was scraped bedrock, which in places rose up in ledges higher and more steeply angled than the meanest speed bumps imaginable. The truck reared up until the hood blocked the view of the ground. Near the summit, when there was a steep drop-off to our right, the road surface changed to loose rocks the size of tennis balls, which were so prone to shifting that they sounded like Rice Krispies as they snapped, crackled, and popped beneath the wheels.

On the other side of the ridgeline, we entered a narrow canyon cut by a creek that was as dry as the moon; water for the livestock had to be pumped over the hills from a well near the river. Brush closed in on the road. Red told us that long ago the land had been cleared by wetbacks. “I know I’m not supposed to use that word,” he allowed, “but do you know a more descriptive one? They aren’t aliens and they oughtn’t to be illegal. In my experience, I’ve only known one Mexican who came here to do mischief. The rest came here to better themselves. They were good for this country. They did a lot of range improvement that a small rancher can’t afford to have done today. Nobody complained until they went to the urban areas and began working in jobs that paid more money.”

The road ended in a bowl whose only opening was behind us, the creek’s escape to the Nueces. We were surrounded by highlands—off to the left, ridges of gray limestone, and off to the right, the highest hills I had yet seen, two of them topped by great domes of rock. Cedar occupied the lower slopes but never the upper, and the extent of its advance was as linear as a timberline in the Rockies. On top of the ridges the only thing that grew was sotol, and I could see the blooms of its tall stalks outlined against the sky. It was an extraordinary place, marred only by the sickly yellow tint of much of the vegetation, the color of impending death.

Red and Carl had come to repair a livestock pen. Normally this would be the lessee’s responsibility, but a clause in the lease allowed the Stoners to use the area if the lessee had fallen behind on his payments, which he had. Gil’s brother, who lives in Hondo and works in San Antonio, was keeping a few cattle on the land, and the pen’s sagging fence needed to be strengthened in case the Stoners had to round them up. Red grabbed a fifty-pound sack of feed from the truck bed as easily as if it were a pillow and poured its contents on the ground to keep the cattle occupied while the two men worked. He put on heavy gloves, unrolled the wire fencing, and yanked it repeatedly until it was taut around the trees and cedar posts. Then he used the smaller pieces of wire to tie the new fencing to the old. He bent over, squatted down, stepped spryly over low points in the fences. Carl was at least a quarter of a century his junior, but when it came to work, they were peers.

The two men took no water breaks and said almost nothing to each other for more than an hour. It was too hot, and the work was too hard, for conversation. Midway through, Red said, “Well, it’s looking a little better.” “Yeah,” Carl answered. “It’s going to work.” Then, more silence. When they had finished, Carl looked over what they had done. “I reckon it will hold a sheep or a goat,” he said, “for a while anyway.”

DROUGHT IS A SLOW, INEXORABLE killer, but four days after Gil’s roping clinic, it exacted a swift and terrible toll on the Stoner Ranch. Gil usually feeds coastal hay to the horses, but coastal is hard to find this year, so he bought alfalfa instead. A day after eating it, six horses stopped feeding—a sure sign of sickness. They had ingested blister beetles, which are attracted to alfalfa when it blooms. The beetles are hard to detect because they may be deep inside a bale, smothered to death but still toxic. Their poison can kill horses at once, or it can cause them to founder so badly that they can’t stand on their legs, in which case they have to be destroyed. I learned of the crisis from Amy when I called to confirm my next visit to the ranch. Three of the horses had already recovered; three were still at the vet’s, prognosis poor.

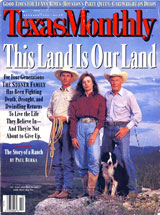

I arrived the next day, driving most of the way from San Antonio to Uvalde through a steady rain. Hurricane Dolly had gone ashore in Mexico, and the outer squalls were dumping rain on Texas. But the storms had never made it as far as the Nueces River Canyon: The dirt road to the Stoner Ranch was as dusty as ever. Gil and Amy had gone into Uvalde to see the vet, and Red was waiting for me at the ranch house. He ushered me into the living room and lit up the inevitable Pall Mall. Amy has added her touches to the house that had been a male domain for three decades, but the living room has remained as it has always been—a cowhide area rug, deerskins thrown on the chairs, a serape over the sofa, a full gun rack, more guns leaning against a wall, deer heads on the walls, rodeo trophies and pictures of horses everywhere.

While we waited to learn the fate of the horses, Red told story after story about ranching and family lore. His mind was an almanac of lost arts: protecting newborn goats, laying water pipe, living on credit at the general store. Every story seemed to carry a little moral. Of Carl he said, “He’ll do his share and a little bit more. That’s the way it’s supposed to be, but there’s not enough of that in this country these days. At the same time, he’s not a man I’d like to have mad at me. I guess that’s the way it’s supposed to be too.” He talked about Anna, her daughter (“the best sidesaddle rider I ever saw”), and his three children, Gil and Tom and their sister, Jamie, who own the ranch jointly. Red rated Tom as a better natural rider than Gil, but Gil was more driven. “A great horse trainer has to be a perfectionist,” he said.

At last we heard Gil and Amy driving up the road and went outside to the sight of boiling storm clouds in an evening sky. The news from Uvalde was mixed: two of the sick horses would make it; one would not. It could have been better, but at least it wasn’t worse—the story of a rancher’s life, it seems.

For a while the blue-black clouds appeared to be going around us to the southwest, but then the wind changed, and fresh, cooled air pressed hard against our faces. It was that delicious moment when you know that rain is inevitable.

“It doesn’t get any better than this,” said Gil. “This is why the whole United States has fallen in love with the West. When I was in Houston, you didn’t dare wear a cowboy hat to school. Now, people in the city work all their lives as doctors and lawyers, just to have this. To them there’s nothing as romantic as a ranch.”

“Romantic?” asked Amy. She rolled her eyes.

I asked Gil what his wish list was for the ranch. “I’d like better quality horses to work with,” he said. “Horses that I picked for a customer, without having to overcome other people’s mistakes. I’d like to plant coastal, put in sprinkler irrigation, and raiser our own feed.”

“That means a new tractor,” said Red. “Twenty thousand dollars.”

The list got longer, new fences, pasture improvement, level the brush in strips to leave wildlife cover, put cement on the road to the back pasture, get the welding machine fixed, repair the cistern, fix up the tack room.

I asked Amy what her wish list included. She rolled her eyes again. “Don’t get me started,” she said.

The first raindrops started to fall. No one made a move to go inside. “I just want to make a living here,” said Gil, “improve the place, let kids grow up in this kind of atmosphere.”

“I don’t see anything changing for the better,” his father said.

“Well, you know what they say about ranching,” Gil answered. “You live poor, but you die rich.” I knew that he wasn’t talking about money.