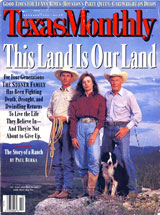

On her new land, Anna managed to make a living by raising goats and clipping their mohair, selling coonskins, and gathering pecans. In time she and her son Thomas Royal were able to add to the ranch until it stretched far back into the steep, forbidding hills that form the divide between the Nueces and the Frio. Still, by Hill Country standards, the Stoner Ranch was small—one that might support a single family but not a clan. Children grew up, left, wanted to be bought out by siblings who stayed. Red Stoner took over from Thomas Royal, his father, in 1960, and it took him nearly two decades to get out of debt incurred in a buyout of his brother. Eventually, Red sold off eight hundred acres on the east side of the ranch and land he owned personally that encompassed Round Mountain, the only freestanding butte in the Nueces River Canyon. But as hard as times have been for recent generations of Stoners, at least it used to be possible to make a living by ranching. Today, drought, isolation, and low livestock prices make it hard even for the big ranches to survive. The federal government has ended its subsidy of mohair and made it illegal to hire undocumented Mexican immigrants, who for decades made up the labor force in the South Texas ranch country. Gil knows that the odds are against him. But they were against Anna too.

A BLACK IRON SILHOUETTE OF A MAN on horseback marks the entrance to the Stoner Ranch off lightly traveled Texas Highway 55. Recently a second sign has joined the first. Made of wood, with a small rope looped around the perimeter, it reads: “Stoner Ranch—Founded 1884. Primitive campsites * Cabin * fish * Swim * Tube * Hike * Bike * Canoe * Birding.” This is ranching in the nineties: The money lies in rounding up people, not livestock.

The people Gil had rounded up on this Saturday morning in mid-August were two boys from a San Antonio suburb. They had arrived the night before, bringing their own horses, and would spend the weekend at the ranch learning how to throw a rope and chasing the Western dream. Weekends are no different from any other days for Gil; they are workdays, sunrise to sunset and after.

The dirt road from the main highway ran through the brush for a little while, then dipped down to cross the Nueces at water level. I sped up, stuck my arm out the window, and felt the cool spray of the spring water. The Stoner Ranch began across the river. My instructions were to drive to the barn, which is two hundred yards east of the ranch house. It turned out to be more of a large tin shed than a classic wood barn, and it was part of a complex that included stalls for the six horses Gil had taken in to train, a round training pen about fifty feet across, and an arena for roping. Gil, Amy, and two boys in their midteens were clustered around a bale of hay lying on bare ground. The hay was a metaphorical cow, and though it was stationary, it would prove to be sufficiently elusive for Gil’s students.

“This is a dangerous, dangerous piece of equipment,” Gil said, brandishing his rope. “If you don’t do it right, you can get tangled up. You won’t have much of a chance before I can get to you with a dull knife.”

The boys, named Cody and Travis, watched him intently as he demonstrated the steps of roping. Approach. Swing. Throw. Jerk the slack tight. Throw off. Gil walked toward the bale, lifted his right arm so that his hand was near his right ear, gave the rope three twirls in a descending arc pointed at the front end of the bale, and let the rope uncoil out of his hand, like a rattlesnake striking. It landed true, draped over the far end of the bale. He pulled it tight, giving his hand a quarter turn counterclockwise, and moved his forearm out to the right to prevent the rope from becoming entangled with his imaginary horse. It looked as simple, and as impossible, as a perfect golf swing.

Gil was teaching the boys calf roping, in which the object is to toss a rope around the neck, but his best event is team roping, in which he aims for the horns and his partner aims for the heels. Team ropers are rated from one to seven and compete against their peers. Pros are sevens. Gil is a six. In 1993 he won the state championship in his division and with it a $6,000 prize and a fancy horse trailer. In smaller rodeos, though, there are fewer divisions and sixes usually have to compete against the pros, who can afford the top horses and the entry fees. At one time Gil’s ambition was to go on the rodeo circuit as a roper. But you need a sponsor or a patron or independent wealth to be able to make it as a professional, and Gil was oh-for-three. Still, he has enough of a reputation regionally that he has been holding roping clinics for five years.

The boys stood at opposite ends of the bale and took turns trying to rope it. Gil barked out instructions: “Stop! Your loop is too big… . Go right at him, like a snake would… . You’ve got to get more speed on it… . No, no, no! Stay forward. Don’t step back… . Don’t drop your elbow. You’re going with your body first. Go with your arm first.” In ordinary conversation Gil has a matter-of-fact tone with little emotion or inflection, but when he is working, with horses or with people, he is in command mode.

Cody was the first to catch on. He was the taller and leaner of the two, and he seemed more at home in the country than Travis did. When his rope caught a corner of the bale and stuck, he looked up for approval. “Yeah!” cheered Amy, who was sitting on a cut log, her chin resting on her hands, her long auburn hair flowing out behind her whenever an occasional breeze kicked up. Travis missed again. “Close, close, close,” said Gil, generously. Another half an hour passed before Travis hit three in a row. That was good enough for Gil. “Let’s go to the arena,” he said. “You’ve got to ride right too.”

Red Stoner was waiting for us at the arena. He is 78 years old and even lankier than Gil, with a long, long face, thick eyebrows, and weathered skin. His nickname could have come from his hair, mostly gray now but still flecked with color, or his ruddy complexion. He smoked Pall Malls incessantly, using a cigarette holder, and never once coughed. I had met him on an earlier visit, indoors, where he seemed old and weary, his eyes opaque and his hearing poor, but outdoors it was a different story: He was active, agile, and keenly observant. While the boys were roping the bale, he had maneuvered thirteen steers into a chute, where he could release them one at a time for the boys to chase. They were small Mexican cattle—four-hundred-pounders, tough and wiry, that Gil keeps for roping practice—and they crowded up against each other, ducking their heads and horns under the legs of the steers in front of them, bawling their complaints.

Red took a long look at the boys riding in on their horses. “I think we’re going to have horse trouble,” he said to me. “Those horses are overfed and underexercised.”

We had horse trouble. Travis’ mount wouldn’t enter the U-shaped area next to the chute, known as the box. The horse acted as if he had never seen cattle before, and maybe he hadn’t. He wouldn’t even look at them. The more he balked at going into the box, the tighter Travis pulled the reins, causing him to back up. “No, no, no!” Gil shouted. “Keep him moving forward. Turn him.” When Travis finally pulled left on the reins, the horse turned grudgingly, fighting it all the way. Gil told Travis to take him out into the middle of the arena and keep him going left. The horse gratefully left the box and went into a circle. One circle. Then he ran off to the right. “No!” Gil yelled again. “Don’t let him do what he wants to do. Make him do what you want him to do. Keep him going left until I tell you to stop.”

Cody was having trouble too. Gil walked over to talk to Red. “This isn’t going to work,” he said. “These horses need to get rid of some energy.” The roping was over for the morning; Gil and the boys were going into the hills on horseback. I remembered something he had told me a few days earlier, on my first visit to the ranch. He had just finished training a filly, a session during which he stood in the center of the round pen and directed it to trot in a circle just by lifting an arm. “Horses don’t get ridden like they used to,” he said. “Almost every horse I get in here, I have to start by undoing people’s mistakes. A horse isn’t made like a human being. In nature they run in herds. They have long skinny legs and eyes on the sides of their heads because they’re prey animals, and you have to convince them that you’re not a predator. Most horses either fear people or don’t respect them enough. Whatever’s wrong, it’s always the human’s fault.”